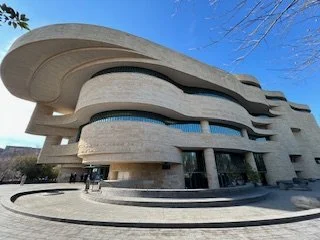

A Visit to the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI, Washington DC.)

I recently visited NMAI with my friend Paulette Fairbanks Molin and her husband Larry, the day before her brother was to have a Navy ship named after him. (see previous blog) As you approach the museum, the unique shape of NMAI is a welcome contrast to the angular grey buildings nearby. Its round contours draw you into the circle of Indigenous life. Quarried from Minnesota stone, its warm brown appearance welcomes you.

Once inside, you look up and see concentric circles reaching to the sky.

Douglas Cardinal, a Native architect collaborated with others to create a building and site aligned to the four cardinal directions. When the museum opened twenty years ago its mission was to foster Native cultures by “reaffirming beliefs, encouraging contemporary artistic expression, and empowering the Native American voices.”

Historical Information About the National Museum of the American Indian

NMAI is one of three facilities operated by the Smithsonian, which grew out of the massive collection of objects of the Native Americas collected by George Gustave Heye during the first half of the twentieth century. Heye’s original intent was to preserve, study and exhibit all objects connected to the “aboriginal Peoples of the Americas” and he amassed over 700,000 objects. When the museum transferred to the Smithsonian in 1989, it switched emphasis to partnerships with Native peoples. New exhibits were developed to portray contemporary lives and the museum began to work with Native community representatives, scholars, and artists. Today there is also the Gustave Heye Museum in New York City and The Cultural Resources Center in Maryland, where scholars conduct research and preservation.

In 1990, Federal government passed a law that provides for “the protection and return of Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. This law recognizes that all human remains, and other cultural items must be treated with greatest respect, and they should be returned to lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations.

This law seeks to encourage dialogues between museums and Indian Tribes and to promote a greater understanding between the groups as they try to negotiate how to best preserve and determine where objects belong. NMAI now does this through their Shared Stewardship and Ethical Returns Policy, which states they will work with “individual, descendent communities in shared stewardship and potential return based on ethical decisions” This paves the way for repatriation when appropriate.

Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indians

We focused on two major exhibits, Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations was the first. The museum uses the treaty exhibit to teach Indigenous history and goes from the first treaty, through contemporary relationships with the United States government. One important goal of this exhibit is to portray Native leaders’ roles in diplomacy.

Outside the exhibit halls, tribal flags of many nations are hung, with the Haudenosaunee flag leading the way.

Haudenosaunee Flag - Nancy Kraus

The Haudenosaunee are given this honor because of their early treaty making and because the Haudenosaunee created the two-row wampum, or Gaswéñdah,. This belt signifies that the Europeans and the Haudenosaunee would travel two non-intersecting paths allowing each to lead their own lives. The belt features prominently in the exhibit with an enlarged replica of the belt encircling the top of a main exhibit hall. The Treaty of Canandaigua from 1794 is also a major piece in the display. At the original treaty signing the leaders of the six Haudenosaunee nations signed the treaty and over 1500 members of the nations were in attendance. You can go to the commemoration in Canandaigua every year on November 11.

To read more, see Ganondagon.org.

Photo Credit: Angelina Hilton

The Americans: Stereotypes and Their Impact

The other major exhibit we visited, The Americans, was of great interest to Paulette and me. When I worked with Paulette in the Indian Elementary Curriculum Project in Minneapolis Public Schools and later in the St. Paul Public Schools’ Native American Resource Center, an important focus was teaching about Indian stereotypes. Paulette co-wrote with Arlene Hirschfelder and Yvonne Wakim Dennis the book, American Indian Stereotypes in the World of Children: A Reader and Bibliography (second edition).

The museum states that The Americans exhibit images of American Indians “are everywhere. Pervasive, powerful, at times demeaning, the images, names, and stories reveal the deep connection between Americans and American Indians as well as how Indians have been embedded in unexpected ways in the history, pop culture, and identity of the United States.”

The large exhibit hall overwhelmed me with its fictionalized images of Indigenous people. It was hard for me to get beyond the negative feelings these images generated because of their inaccuracy of either presenting the romantic idealized version of an Indigenous person such as the Land of Lakes Indian Princess or the savagery of the fierce warrior image used by many sports teams such as the Cleveland Indians “wahoo.” And then there is Hollywood. With its distortions, savage Indians and horrible cartoons aimed at young children. These images brought back one of the saddest moments I can remember during my teaching career in Minnesota. Maude Kegg, a Mille Lacs Anishinaabe, who devoted her life to making a dictionary of Anishinaabemowin, told us about times when she was working at the Mille Lacs Indian Museum and how children were afraid to enter the museum when they realized “real Indians” were there. Cartoons and movie watching made these children think they would be killed with a bow and arrow or gun if they encountered an Indigenous person. My hope is that this exhibit creates a dialogue for viewers to think how these images impacted them whether the viewers are Indigenous or not.

Other Museum Offerings

When we needed to rest and refuel, we stopped at the museum coffee shop. Although we were disappointed that the Mitsitam Café was closed and couldn’t get to taste more of Dineh Chef Freddie Bitsoie’s creations, the coffee bar offered a few tasty Indigenous dishes. I enjoyed a three-sisters wrap made with corn, squash and beans one day and a wild rice salad with a corn muffin the next day.

If you are in Washington D.C. don’t miss this museum. If you can’t get there in person there are many wonderful resources from the museum online including an educational packet about the Haudenosaunee. You can also sign up for excellent educational online workshops which are very helpful to teachers. It is worth taking the time to explore all on their website even after a visit to the museum.